👩💼 Manager hour - the new dynamic world of work 👨💼

Will you really be in this job 5 years from now? Likely, neither will your people.

Long stints in one job are no longer a thing, and my research shows that it applies even to senior managers and executives. If you're interested to learn more - read on.

We've entered a new world of work where people are much more dynamic at navigating their careers. Doing a bit of number-crunching, I discover that this applies not only to individual contributors but to managers as well, and even executives!

Preamble

We've all been seeing cries that "employees are just not loyal" anymore for a while. A quick Google search brings a flurry of articles with flashy titles:

Many of those articles focus on individual contributors and how management needs to work better to retain them. But what if everyone just got more mobile? Looking at my own history and many of my peers - it seems so. But can I verify that somehow? I think I can.

Methods

After some spelunking, I’ve found a randomised public LinkedIn dataset, including about 10000 public profiles from the US, Canada, India, Israel, Japan and Singapore. To not overload my poor laptop, I rented a couple of hours of machine time at Paperspace and used RAPIDS as I wanted to play around with GPU-accelerated data science for a while, and this seems to be the perfect excuse.

After loading and parsing all the work experience data, I analysed over 140.000 individual work experiences across seven countries. I did some RegEx-based matching across the title names to separate management positions from IC positions, as well as assign some "flavours" to management positions, e.g.:

Line/Middle management - matching "manager" and "senior manager" titles. With some indication of people responsibility, i.e. filtering out things like account managers, program managers, etc.

Senior managers - matching miscellaneous "director" titles.

Executives - matching miscellaneous "VP" and "president" titles.

C-Suite - matching all C-Suite positions.

Then, I calculated the ranges for each full experience. I.e. one that had a start and end date specified on LinkedIn. This means that the lateral/vertical moves within the same company are considered to be a different position, but I think it fits with our purposes.

There are some known caveats:

This used fuzzy matching, so the data is by no means perfect.

The few profiles with non-English titles get skipped (esp. in the Japanese dataset)

There was no specific sampling or bucketing of data by years.

The Python notebook is published here if you want to examine my methods more closely.

Results

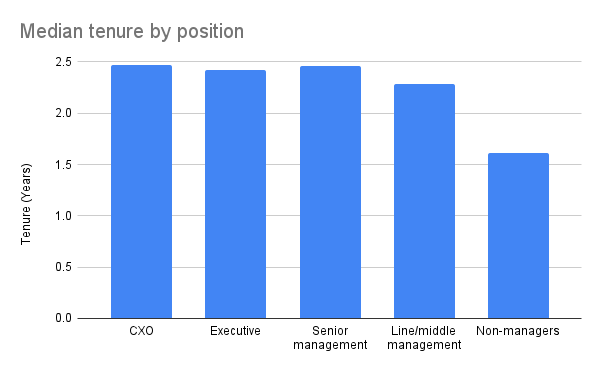

If I average all the collected experience data, I get a fascinating picture. The median tenure of management is higher than your average IC, granted, but it's still less than three years!

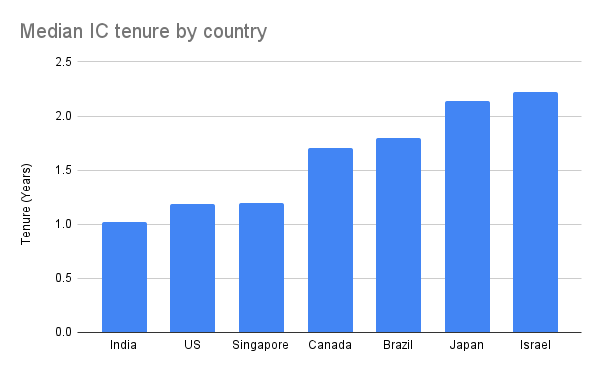

If I look into data by country, some interesting things start to show up. First, looking at ICs, it seems like the workforce in the US is one of the most mobile, and Israel shows one of the best median retention scores.

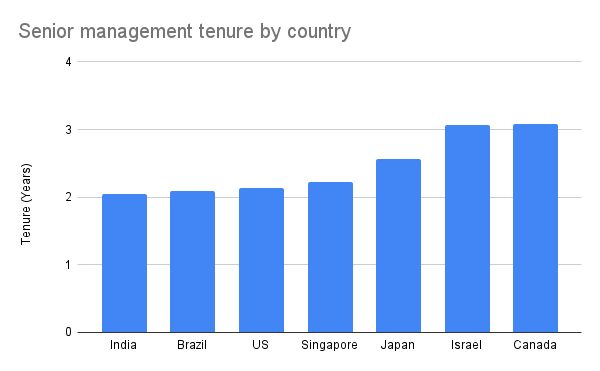

And this isn't limited to ICs, either! Line management is also very mobile, with just a couple of months over average tenure, with senior management and executives not too far ahead.

It looks like even C-Suite is not excluded from the pattern. Emerging markets show tenures being less than overall management, presumably due to a higher rate of entrepreneurship.

Conclusions

It looks like we have indeed entered a new dynamic world of work. But what now? I think I can make some valuable conclusions that will help us create a better working environment for people.

You should not count on people to spend over three years in one position, manager or not. It's still possible for them to do so, but you shouldn't bet on it.

Make sure you adjust your development strategy for it. Throw out those five and ten-year development plans and make something that helps the person get into their next role in 2 to 3 years. This may make the difference between retaining a great employee or leader and losing them to the competition.

You should have succession plans that work off the same assumptions. This is especially critical for executives as hiring and onboarding take much longer at those levels.

If you want to grow successful people - equip them for a career, not a job. Let them develop broadly valuable skills. Allow and encourage internal mobility - the company and the employee will both be better off for it.

Improve your onboarding and tools. If it takes a person six months to fully get up to speed and learn clunky tools, you just spent half-to-a-quarter of their tenure on onboarding.

Help your leaders get up to speed quicker. Have succession and transition plans in place. Give more autonomy and flexibility to your middle management. Have a good strategy in place. Create a safe and calm working culture resilient to changes.

Opinion

I asked the wonderful Anne-Marie Charrett from Sydney Technology Leaders to give her take on the data, and she has graciously agreed ❤️

"This data confirms my personal experience. I have not worked longer than two years at any organisation. What's interesting is the CTO data. From my experience in Enterprise - a CTO's role is typically around the 3-to-4-year mark. They build the business up, make a name for themselves and then move on to bigger things, so no surprise there.

But time and time again, I see startups and scale-ups offer CTOs extensive share options because they want to retain them for a long time ("have some skin in the game"). The reality is, though, you may need a different set of competencies later. The profile for a startup CTO and a scale-up CTO are very different. That person can be both, but it's rare and requires much effort. This data reinforces my belief that not all CTOs are (or should be) alike and that different times in a company's lifecycle need different skill sets.

On the engineering front, I believe that, unlike puppies, engineers are not for life. Think more about outcomes and less about timeframes. By hiring an engineer, what outcome do you want? Achieving that is the goal, not the number of years at a company. We can't predict the future, but in this way, we can prepare for it."

Follow her on annemariecharrett.com for more!

Do you agree? Disagree? Want to explain just how bad my Python is? Let me know in the comments!